There are no items in your cart

Add More

Add More

| Item Details | Price | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Sun Jan 11, 2026

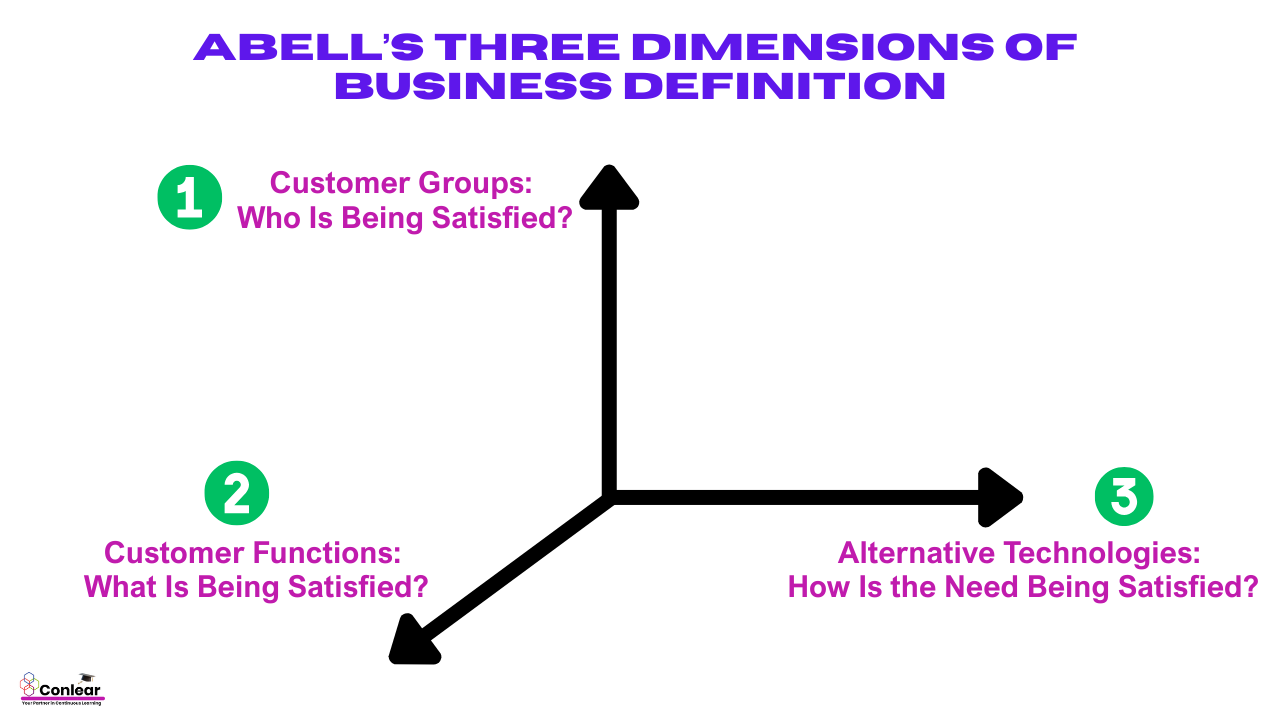

One of the most fundamental questions in strategic management is deceptively simple: What business are we in? The way an organisation answers this question shapes its objectives, strategic choices, organisational design, and long-term direction. Derek Abell’s path-breaking analysis provides a structured and market-oriented way of answering this question by defining business along three interrelated dimensions. Abell argued that businesses should not be defined narrowly in terms of products, but more meaningfully in terms of customers, their needs, and the technologies used to satisfy those needs. This perspective helps managers avoid strategic myopia and enables them to think more clearly about growth, diversification, and competitive positioning.

According to Derek Abell, a business can be defined along the following three dimensions:

Together, these dimensions provide a comprehensive framework for understanding the scope and boundaries of a firm’s business.

The first dimension of business definition focuses on customer groups. Customer groups are created according to the identity of customers and answer the question: Who is being satisfied?

Customers can be grouped in many ways—individual consumers, businesses, institutions, governments, or even specific segments within these broad categories. For example, a financial services firm may serve retail customers, small businesses, and large corporate clients. Each of these groups may have different expectations, risk profiles, and service requirements.

By explicitly identifying customer groups, managers gain clarity on who the firm exists to serve. This clarity is critical because different customer groups often require different value propositions, pricing strategies, and service models. A vague or overly broad definition of customer groups can result in unfocused strategies and inefficient resource allocation.

From a strategic perspective, customer groups also define market boundaries. Decisions such as entering new segments, exiting existing ones, or prioritising certain customers over others all stem from how customer groups are defined.

The second dimension relates to customer functions, which focus on the needs, problems, or benefits that customers seek from a product or service. This dimension answers the question: What is being satisfied?

Customer functions are not the same as products. Products are merely vehicles through which customer needs are fulfilled. For example, customers do not buy a drill because they want a drill; they buy it because they want a hole in the wall. The underlying function is the ability to make holes, not the ownership of the tool itself.

Customer functions may include convenience, safety, cost savings, status, comfort, speed, or reliability. A single customer group may seek multiple functions, and different customer groups may seek similar functions in different ways.

By focusing on customer functions, firms are encouraged to think beyond existing offerings and identify latent or evolving needs. This orientation is particularly valuable in dynamic markets where customer expectations change rapidly. It also helps firms recognise substitute solutions that may not look like direct competitors from a product-based viewpoint.

The third dimension of Abell’s framework is alternative technologies. This dimension describes the manner in which a particular function can be performed for a customer and answers the question: How is the need being satisfied?

Technology, in this context, should be interpreted broadly. It includes not only physical technologies but also processes, platforms, delivery systems, and business models. For example, the customer function of “access to information” can be satisfied through books, newspapers, television, websites, mobile applications, or artificial intelligence-based assistants.

Focusing on alternative technologies helps managers recognise that the same customer need can be fulfilled through multiple technological routes. This insight is critical for anticipating disruption. Firms that define themselves too closely around a single technology often fail to adapt when new and superior alternatives emerge.

By understanding alternative technologies, organisations can evaluate whether to invest in new capabilities, partner with other firms, or exit declining technological domains.

Abell’s framework is not merely descriptive; it has strong strategic implications. A clear business definition can help in the following ways:

In essence, business definition acts as a strategic compass, guiding both corporate-level and business-level decisions.

One of the most important contributions of Derek Abell’s analysis is its marketing orientation. Unlike product-oriented definitions that focus on what the firm produces, Abell’s framework emphasises customers and markets.

A product-oriented firm may define itself by its existing offerings and capabilities, which can lead to rigidity and resistance to change. In contrast, a customer-oriented definition encourages flexibility, innovation, and responsiveness to market shifts. It enables firms to see opportunities beyond their current product lines and to reimagine their role in the value creation process.

Derek Abell’s three-dimensional framework provides a powerful and practical way to define a firm’s business. By systematically examining customer groups, customer functions, and alternative technologies, managers can develop a clearer understanding of their strategic scope and competitive environment.

For students of management, this framework reinforces a critical lesson: strategy begins not with products, but with customers and their needs. Firms that internalise this perspective are better positioned to adapt, innovate, and sustain competitive advantage over time.

Vinayak Buche

Vinayak is the Founder of Conlear Education.